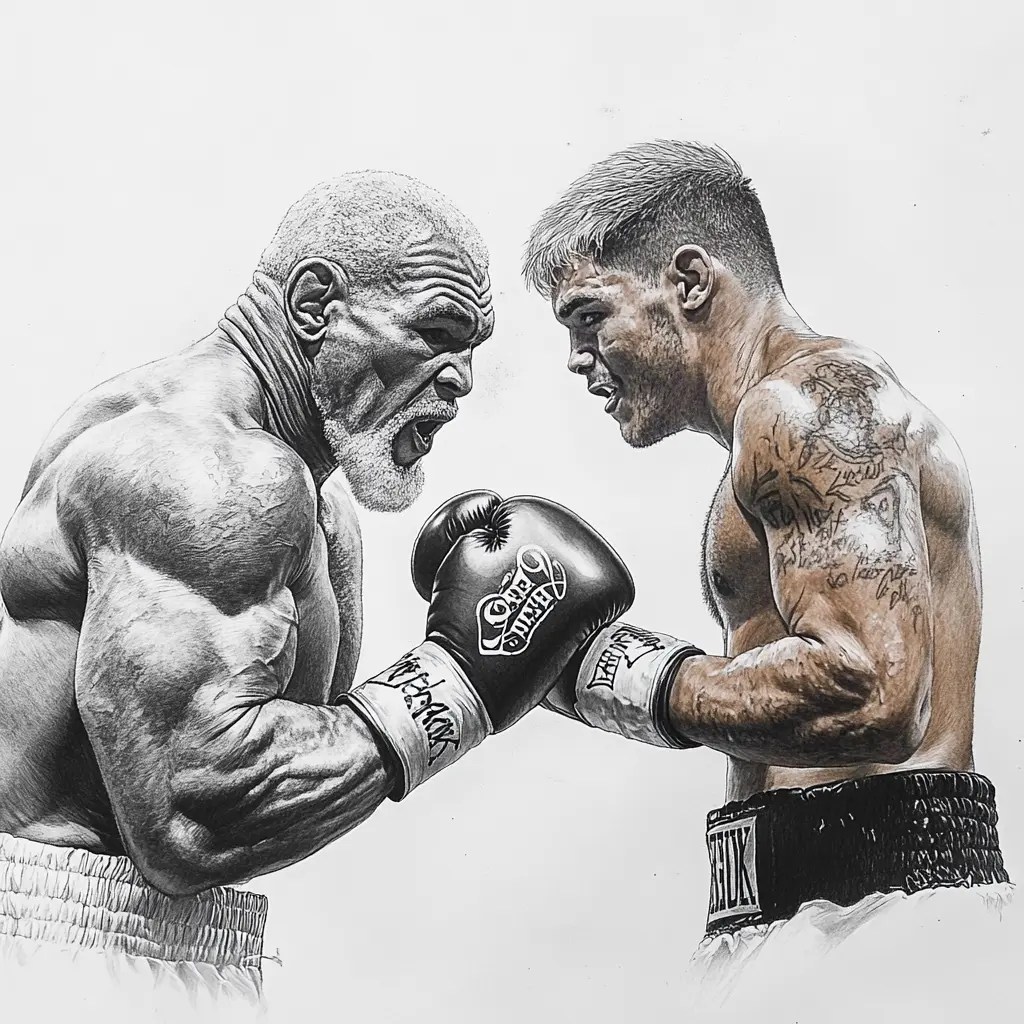

I didn’t sleep well the night between Nov 14th and 15th. Among several reasons, the biggest one was the upcoming fight between Jake Paul and Mike Tyson scheduled for 6:30 AM. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Boxing isn’t particularly popular in India or my social circle, and this wasn’t even a typical matchup: a man who retired 19 years ago facing off against a ‘YouTuber.’

Still, I had my reasons, beyond the obvious hype. It was poised to be the greatest boxing event of the twenty-first century. The world was eager to see if the 58-year-old “still had it”. He was supposed to lose. But we love miracles.

Even Jake’s supporters likely hoped for one. After all, expecting someone who first wore boxing gloves well into adulthood to win against a former ‘baddest man on the planet’ seemed absurd. Mike, however, wasn’t the same man from his prime; he was only a percentage of that legend. The question was: “What percentage?”

For me, the fight was more than just entertainment. I was looking at it as a case study of the effects of aging, particularly through the lens of what Peter Attia calls the “four horsemen” – metabolic diseases, heart disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. I saw it as an opportunity to connect the dots from that branch of literature in the vaguest possible sense.

- Redundancy in the Human Body

- Aging, Decline, and Regeneration

- The Fight was a Metaphor

- Lessons on Redundancy and Resilience

- Redundancy and Antifragility

- Conclusion

Redundancy in the Human Body

Systems like the human body, by design, have excess capacity. Built to survive loss, this design allows partial failures without complete collapse. Can you survive losing a few liver cells, a few neurons, one finger, a limb, a kidney?

The answer is yes in most cases. We have redundant units of each. But there’s a cost – what remains must work harder to compensate. This increased stress accelerates further failure. This stress compounds: the more cells lost, the faster the next one goes.

Let me show you a practical experiment. I’m attempting a simple motion in the video, what you would call a pull-up. Each time I attempt, I reduce one finger from each hand. See the results:

The difference between five fingers and four in grip strength is hardly noticeable; with three and two – the difference is pronounced. At one, the system fails completely. Of course, it is for my current level of fitness which would vary cross-sectionally (who attempts) and temporally (when).

This redundancy is why Tyson could still box at 58. His body compensated for decades of wear and tear. But how long could it sustain under the pressure of an eight-round fight? That’s where aging and the four horsemen come into play.

Aging, Decline, and Regeneration

Ageing isn’t linear; it’s like the negative side of marginal utility we usually study for the economy. Each additional unit lost causes a much greater impact than the previous one – negative compounding. For example, a 27-year-old loses far less physical ability between 27 and 28 than a 58-year-old loses between 58 and 59. Thus, 58-year-old Mike is only a fraction of the man he was at Jake’s age.

But is time the only predictor of performance? If it were, why would Mike accept the fight at all? It isn’t. Two other factors come into play: first, human cells regenerate to some extent; second, the quality of those cells is crucial. Our bodies constantly replace weaker cells with better ones, but this process declines with age. Old cells die and are replenished, but the replacement falls short of the loss, leaving us diminished (killing us, in other words) over time.

The four horsemen of ageing attack the body’s capacity to regenerate, repair, and sustain itself. Mike wasn’t just facing Jake Paul in the ring; he was fundamentally fighting the battle between regeneration and loss. Unfortunately, he had already lost much before this fight began. Several percentages of his physical capabilities were gone before he accepted Jake’s challenge. He could never regain the agility, flexibility, reflexes, and more from his youth. Strength is the last to go, but it’s not enough. His lungs were partly dead, his ligaments and tendons were dead, his neurons were dead, and of course, some muscles, thanks to time and the choices made during it.

The question was, “Was this ‘fraction of Mike’ better than the still-maturing boxer in a young Jake?”

The Fight was a Metaphor

This fight was between the hope of the whole of humanity that youth can be reclaimed or that aging can be reversed and the sobering reality that it cannot.

I’ve spoken a lot about Mike. Though Jake was cast as the heel in the fight, deep down, I wanted him to win, too. Why? Because Jake signified regeneration and growth no less than Mike. He had come a long way, from lame dances to real fights. Jake was ‘hope’ too. He showed that focus, discipline, and hunger added to the sport’s appeal. Despite facing humiliation and hatred simply for ‘being real’, he earned respect.

Mike showed it’s possible to survive eight grueling rounds of pro boxing against a three-decades younger guy who had knocked out top-rated athletes. It showed that, if needed, a retired old pigeon guy can summon his spirit animal (the tiger) with less than a year of training. This fight doesn’t tarnish his legacy, it enhances it.

In the end, both fighters gave everything they had and inspired generations, but time, as always, delivered the final verdict.

Lessons on Redundancy and Resilience

If I were to draw conclusions, I’d say we are fortunate to have more than we need. Wisdom teeth!! Yet, as our stock diminishes, the value of what remains increases, be it bank balance, loved ones, or time.

The abundance of modern life allows us to preserve redundancy. We no longer starve of food or have to struggle for water and energy. We are less reliant on a single server for data storage, or one route (direct or connecting) or mode (air/land/sea) of transport from point A to B.

Yet, as the fight reminds us, even abundant systems have limits.

Redundancy and Antifragility

You cut one head of the Hydra and two grew in its place. Stress made it stronger. Tyson’s muscles showed such antifragility to an extent but had its biological limits. Beyond the limit, it was unlike how IronWorker (a product I sell at Iron.io) auto-scales under heavy load.

Nature did a good job making you sufficiently resilient to partial failure, and we do well replicating them in the technologies we build. The challenge is in recognizing where redundancy ends and fragility begins.

Conclusion

Going back to the question I ventured to answer: “What percentage?”. The answer is: Less than needed to win. Had he known 20 years ago that this fight was coming, he might have prepared better, preserving a higher percentage of his abilities, maybe even enough to win. But he was late.

And in some way, so is everyone for something. Let’s hold on to our redundancies, nurture them, and grow them!

Leave a comment